P4: The last 40 years on the land were revolutionary and disrupted all that had gone before for thousands of years—a radical and ill-thought-through experiment that was conducted on our fields.

P4: The last 40 years on the land were revolutionary and disrupted all that had gone before for thousands of years—a radical and ill-thought-through experiment that was conducted on our fields.

#Naturalitsy

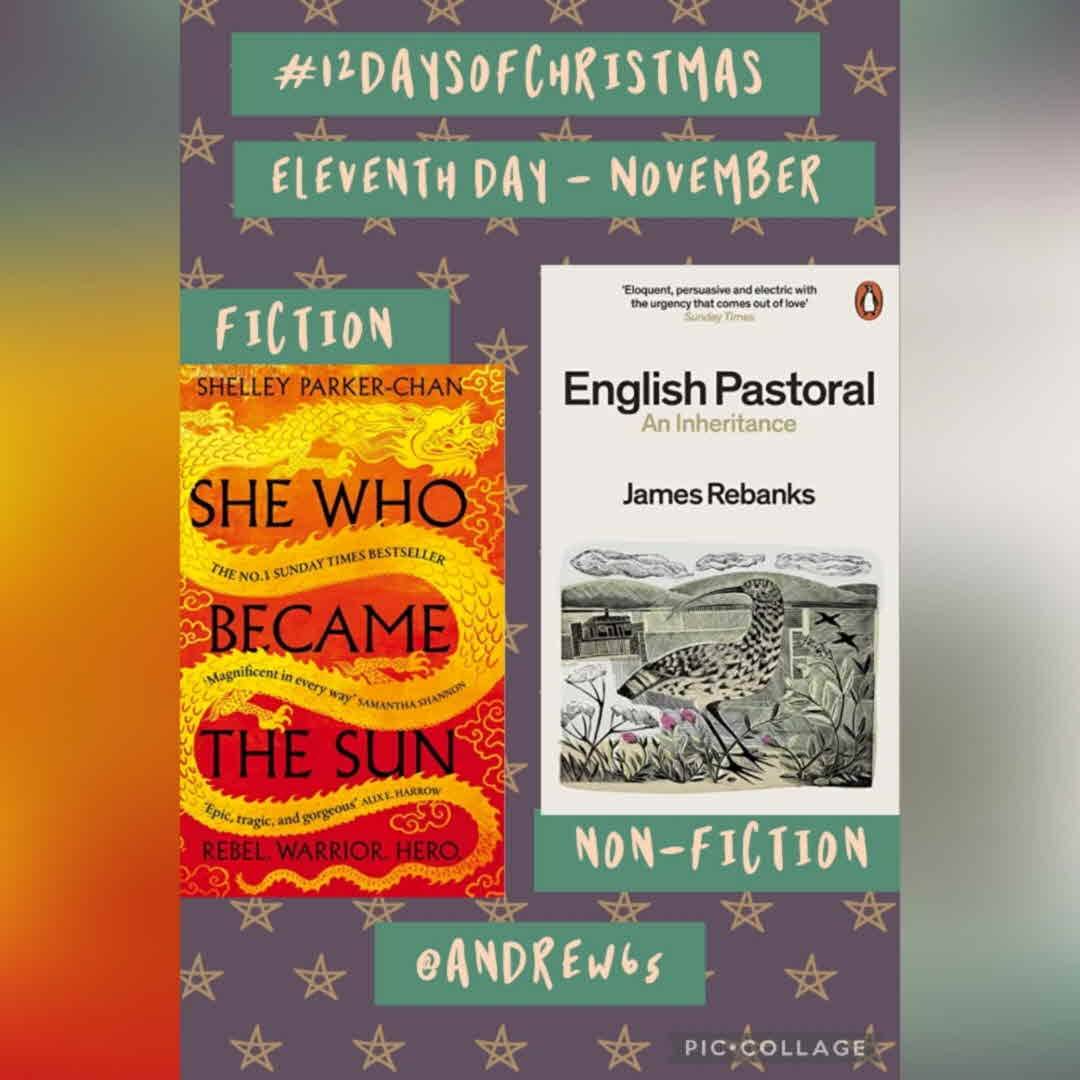

Joining in #12daysofchristmas hosted by @Andrew65

Listing my favourite books of the year over 12 days from my annual fiction and non-fiction reads.

#12booksofChristmas

#NaturaLitsy

This was an amazing read, I enjoyed it immensely. It's a definite best read of 2022. The book is split into different parts, nostalgia, progress and utopia. Each part examines the different methods of farming in the UK. Nostalgia was very reminiscent of my own childhood, found this very moving.

Thank you so so much @jenniferw88 for such a cosy autumnal package. Can‘t wait to get stuck in - the sticky tabs are already earmarked for next years seed catalogue browsing! 👏🏼👏🏼👏🏼. Thank you honey #fallingforfallswap

The economists are wrong. Farming is not a business like any other because, crucially, it takes place in a natural setting and affects the natural world directly and profoundly. As farmers collectively made the land more efficient & sterile, whole species of birds, insects & mammals vanished & ecosystems collapsed. One comprehensive survey spoke of Britain being ‘among the most nature-depleted countries on earth.‘

I‘ve come to understand that even good farmers cannot single-handedly determine the fate of their farms. They have to rely on the shopping and voting choices of the rest of us to support and protect nature-friendly, sustainable agriculture. They need government spending and trade policies to recognize that sound farming is a ‘public good,‘ a thing that needs encouraging and protecting.

By the 1970s the brutal pursuit of industrial efficiency on farms to deliver more and cheaper food became ingrained in agricultural policy across the developed world. There was almost no acceptance in farming or in the political sphere that the insatiable pursuit of industrial efficiency on the land might itself be the problem. Instead, the processes changing farming were increasingly championed as “progress.”

(Internet photo)

There is an old saying that we should farm as if we are going to live for 1000 years. The idea is that we might protect our natural resources better if we had to face the long-term consequences of our actions instead of passing on a mess for someone else to sort out. I find the thought of 1000 years in the future rather daunting and impossible to comprehend. Who is rich enough to be that holy?

The logic chain is simple: we have to farm to eat, and we have to kill (or displace life, which amounts to the same thing) to farm. Being human is a rough business. But there was a difference between the toughness all farming requires and the industrial ‘total war‘ on nature that had been unleashed in my lifetime.

That book changed everything for me. The landscapes falling apart (including ours) were not, as Schumpeter saw it, ‘creative destruction‘ but plain old-fashioned destruction.

I felt as if I‘d woken up from a long coma. I had almost conditioned myself to exclude nature from how we thought about the farm. I had begun to view my grandfather‘s farming with contempt, to pity my father‘s reluctance to modernize. And now I felt like a bloody fool.

I want my children to know how fortunate we are to live in this raggedy old farming valley that is so full of nature. To see—as I did not when I was young—the bigger picture beyond our traditional horizons and think of our farm in its wider setting; to appreciate that no farm is an island, but part of a wider ecosystem, a valley, a river catchment, an interconnected world.

My father wasn‘t much of a churchgoer, but he believed in something similar. He thought that things should have limits and constraints. He believed in moderation and balance. And he died hating what had happened to farming.

I had forgotten how much I love cattle—their clannish ways, their friendliness and their constant munching.

[Supermarket shoppers] seemed not to know, or care much, about how unsustainable their food production is. The share of the average American citizen‘s income spent on food has declined from about 22% in 1950 to about 6.4% today. The proportion of every dollar spent on food that goes to the farmer has declined massively to around 15 cents & is still declining. The money almost all goes to those who process the food & to wholesalers & retailers.

Supermarkets were advertising low-priced milk as part of a price war at that time. Dairy farmers couldn‘t afford to stand still as the real price fell—the price of milk was lower than that of bottled water.

Every meal featured potatoes: they were peeled on a Monday, plopped into a bowl of water for the whole week, and brought out to be mashed, boiled, chipped, sautéed, fried or roasted. The ‘leftovers‘ were cooked again.

I loved firing the milk from the teat into the foamy warm milk in the bucket, loved the soft frothy drilling noise it made.

(That‘s my sister Simone in the photo.)

The UN says that 5 million people move from rural communities to urban ones every month, the greatest migration in human history. […]

And yet we are all still tethered to the land in a practical sense—our entire civilization relies on farming surpluses, which free most of us from growing our own food, allowing us to do other things.

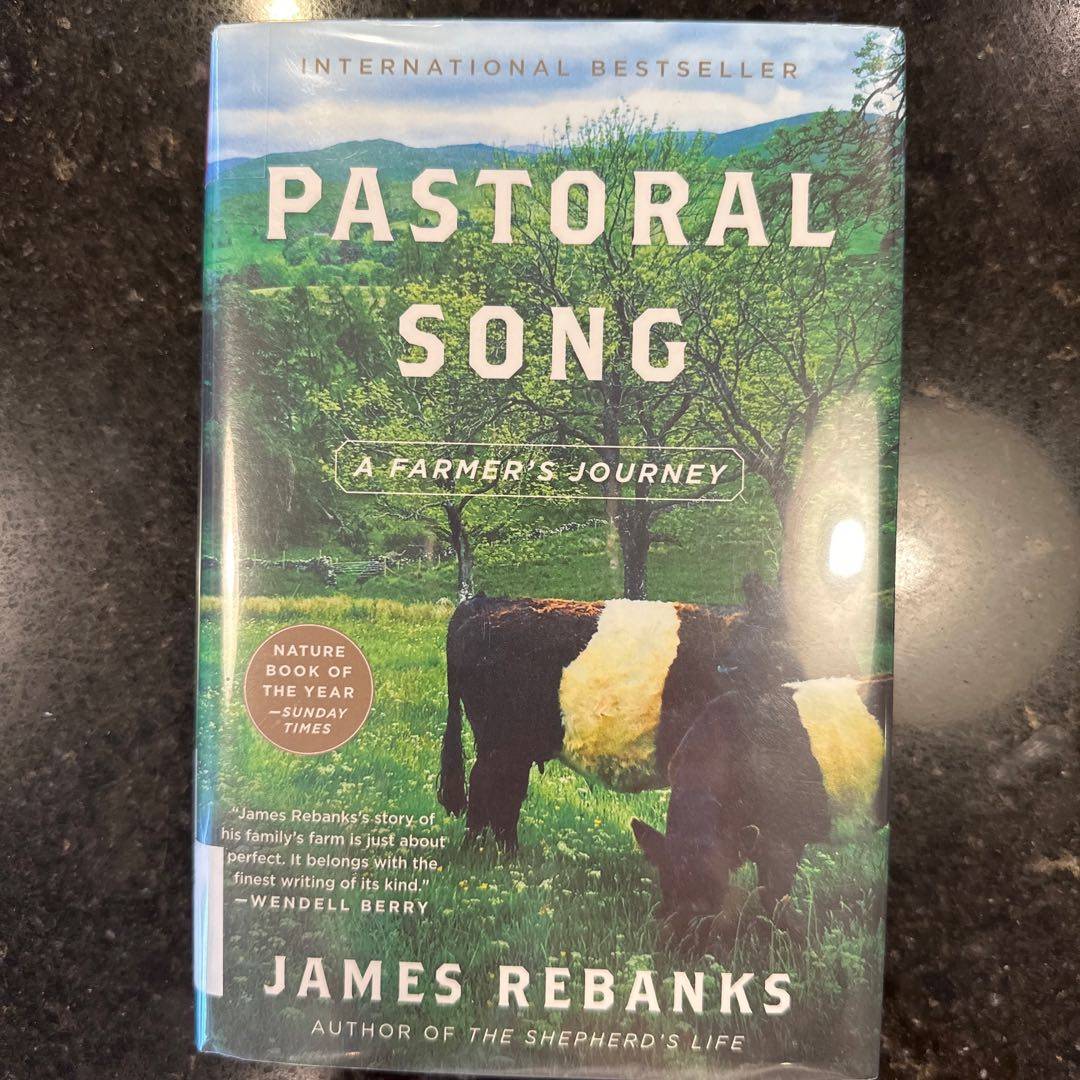

It took 22 days to travel by post to Edmonton from a bookshop in Halifax, but it‘s finally here!