Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens | James Davidson

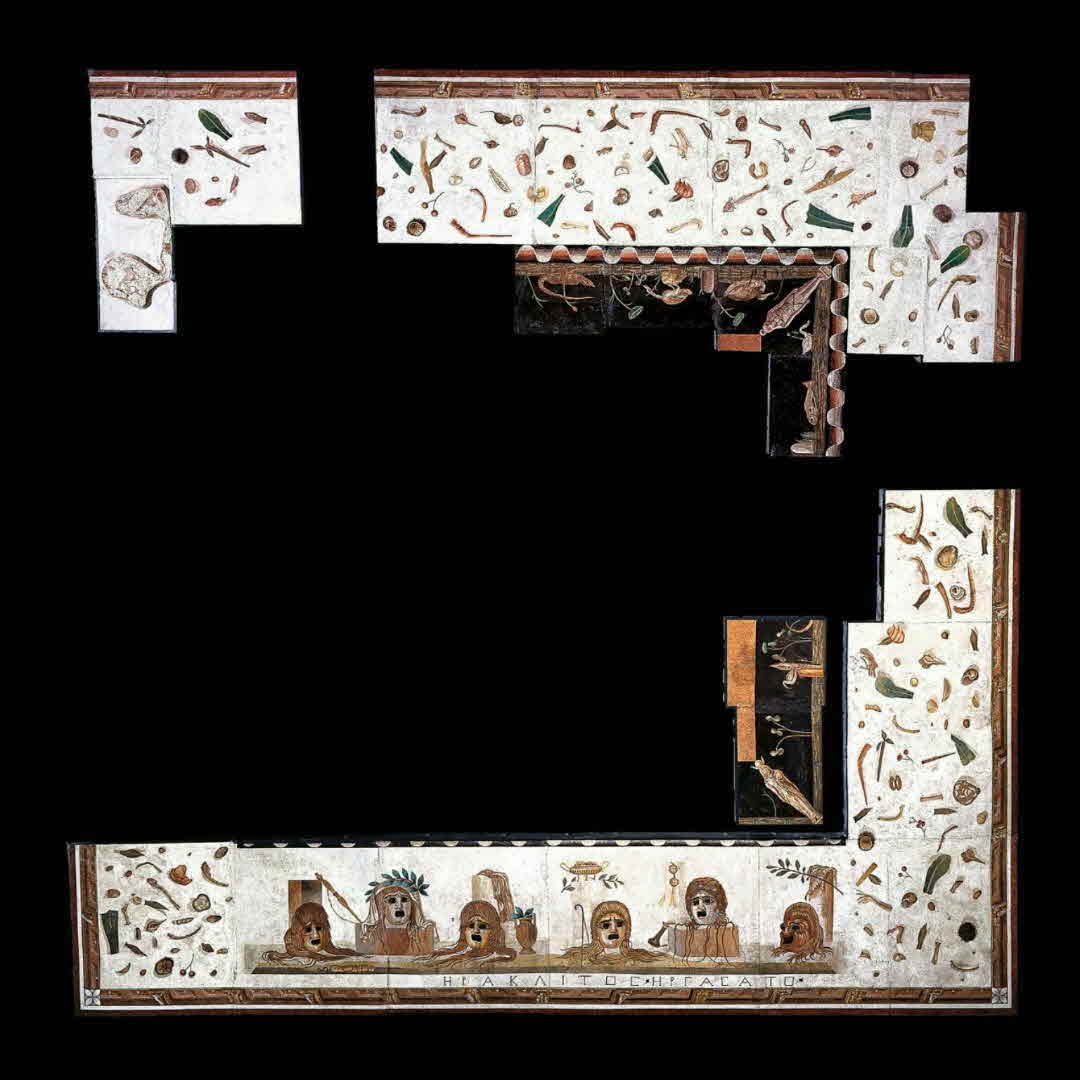

Part OneEatingThere was a banquet and people were talking and, as so often in accounts of banquets at this period, Socrates was there. The topic was language: the origin of words and their true meanings, their relationships with other words. In particular, according to Xenophon, who describes the scene in his "Memoirs of Socrates," they were talking about the labels applied to people according to their behaviour.' This was not in itself an uninteresting subject, but failed nevertheless to absorb Socrates' complete attention. What distracted him was the table-manners of another guest, a young man who was taking no part in the discussion, too much engrossed in the food in front of him. Something about the way the boy was eating fascinated Socrates. He decided to shift the debate in a new direction: 'And can we say, my friends, ' he began, 'for what kind of behaviour a man is called an "opsophagos?'"FishIf Plutarch had been present (and Plutarch would have given anything to be present had five centuries not intervened) the question might have been a non-starter. For Plutarch is quite categorical: 'and in fact, we don't say that those, like Hercules, who love beef are "opsophagoi" . . . nor those who, like Plato, love figs, or, like Arcesilaus, grapes, but those who peel back their ears for the market-bell and spring up on each occasion around the fish-mongers." An "opsophagos," according to this ancient authority at any rate, was someone with a distinct predilection for fish. 'But if you go to the prosperous land of Ambracia and happen to see the boar-fish, buy it! Even if it costs its weight in gold, don't leave without it, lest the dread vengeance of the deathlessones breathe down on you; for this fish is the flower of nectar.' The Greeks were fond of fish. Fondness, on second thoughts, is rather too moderate a word for such a passion. What the literature of pleasure manifests, time and time again, is something rather more intense, a craving, a maddening addiction, an indecent obsession. The flavour of this yearning is easily sampled in the work of Archestratus of Gela in Sicily, from whom the eulogy of the boar-fish is taken. Another passage from the same work advises readers on what to do if they come across a Rhodian dog-fish ("E missole?"): 'It could mean your death, but if they won't sell it to you, take it by force . . . afterwards you can submit patiently to your fate." Archestratus acquired a certain amount of notoriety for his mock-heroic hexameters rhapsodizing food, but his work, variously known as "Gastronomy, Dinnerology" or "The Life of Luxury," was by no means untypical of the discourse of gourmandise. What should be noted is not so much the extravagance of the language used to describe the fish, as the fact that in a work about the pleasures of eating in general, reference is made to almost nothing else. The Greeks, to be sure, recognized as delicacies some foods which had nothing to do with the sea: some birds and other game (especially thrushes and hares), various sausages and offal (sow's womb was particularly revered), some Lydian meat stews and various kinds of cake, but these were exceptions. The edible creatures of the sea seem to have established a dominance over the realm of fine food in classical Greece that scarcely fell short of a monopoly. It is hard to say who it was who first put the marine into cuisine.The invention of the sumptuous 'modern' style of cookery was usually traced back to the Sicilians or their neighbours across the straits, the people of Sybaris on the instep of Southern Italy. The latter were defeated by their neighbours in 510 and their city was razed to the ground, but stories of their fabulous riches were still being told at Athenian dinner-parties one hundred years later. One historian recorded a Sybaritic law that gave inventors of new dishes a year's copyright (perhaps, says one modem commentator, the earliest patent known). Moreover, he claimed there was a special dispensation that eel-sellers and eel-fishers should pay no tax. In about 572, Smindyrides, distinguished even among the Sybarites for his decadence, had made a great impression when he came over to mainland Greece to seek the hand of the daughter of Cleisthenes the ruler of Sicyon near Corinth. Fearing that the motherland might not be up to his standards, he brought with him one thousand attendants, consisting of fishermen, cooks and fowlers.4 Fish also seems to have been very prominent in the culinary culture of Sicily. According to one source they called the sea itself 'sweet' because they so enjoyed the food that came out of it. Athenaeus tells us of a fish-loving painter from Cyzicus, Androcydes, who painted the sweet fare of these sweet waters in enthusiastic and luxurious detail when depicting a scene of the multiheaded monster Scylla in the early fourth century; we should, perhaps, view the numerous ancient mosaics of marine life with the same perspective we now bring to Dutch flower-paintings, not as cerebral studies in realism, but as loving reproductions of desirable and expensivecommodities. The comic poet Epicharmus, who worked in Syracuse, the island's greatest and richest city, at the beginning of the fifth century, seems to have been preoccupied with sea-food, judging from the surviving fragments, although later writers were not always sure what he was referring to: 'According to Nicander another kind of crab, the colybdaena, is mentioned by Epicharmus . . . under the name "sea-phallus." Heracleides of Syracuse, however, in his "Art of Cookery" claims that what Epicharmus is referring to is, in fact, a shrimp.' In one play, "Earth and Sea," Epicharmus seems to have included a debate between farmers and fishermen, arguing over which element produced the best fare.