“[Lyubov] lay face down in the firelit lake of mud. He did not see a little green-furred huntress leap at the girl, drag her down backwards, and cut her throat. He did not see anything.”

“[Lyubov] lay face down in the firelit lake of mud. He did not see a little green-furred huntress leap at the girl, drag her down backwards, and cut her throat. He did not see anything.”

“Raj Lyubov‘s job was to find out what [men] did …he lreferred to be enlightened, rather than to enlighten; to seek facts rather than the Truth. But even the most unmissionary soul, unless he pretends he has no emotions, is sometimes faced with a choice between commission and omission. ‘What are they doing?‘ abruptly becomes, ‘What are we doing?‘ and then ‘What must I do?‘”

Halfway through, but thoroughly nejoying Le Guin‘s constant links between societal structure snd linguistics. A very simple one being the literal title of the book, the word for dream being the same as root, the ‘two meanings in one‘ concept she uses the highlight the fundamental differences between Terrans and Athsheans‘ perception of life. We both experience this in the narration whilst also experiencing Lyubov experience it with us.

“…But the men won‘t bring women to the Forty Lands until they had made a place ready for them.” “Until the men made a fit place for women? Well! They may have quite a wait…They should have sent the women first. Maybe with them the women do the Great Dreaming? Who knows? They are backwards, Selver. They are insane.”

“The world is always new…however old its roots…They look like men and talk like men, are they not men?” “I don‘t know. Do men kill men, except in madness? Does any beast kill its own kind? Only the insects. These yumens kill us as lightly as we kill snakes…they kill one another, in quarrels, and also in groups, like ants fighting. They don‘t spare one who asks life.”

“When the Senoi child reports a falling dream, the adult answers with enthusiasm, “ That is a wonderful dream, one of the best dreams a man can have. Where did you fall to, and what did you discover?””

One of the best books I‘ve read - I don‘t have the ability to summarise the vast range of reasons as to why that is the case. From his amusing third person narration obvious obliviousness to character hypocrisies to the book‘s relevance to today in many ways than you‘d think. I am in awe. I wish I could read it for the first time again.

What do men want from me? Why do they pursue me? Why are they so hard? All I am is a perfectly ordinary actor…

“Perhaps you will be more indulgent in death, poor child, than a hard life allowed you to be…For your destiny was accomplished. The end came fast…you summoned it. If it had been otherwise, perhaps you would have gathered around yourself other youths - even more ignorant and younger than you were - and played being conspiratoes with them.”

“He was a blond Rhinelander. His father, too, had been a blond Rhinelander before the financial worries had turned him gray. And his mother Bella his sister Josy were impeccably blond Rhineland women. ‘I am a blond Rhinelander‘ exulted Hendrik Höfgen..It was in the best spirits that he went to bed.”

“The attempt to hand over the Germa people to fascism could end in the socialist revolution…then everyone would see that the actor Höfgen had hambled with cunning and foresight. But even if the N@zis remained in power, what had he, Höfgen, to fear from them?…he wasn‘t a Jew. The fact above all others-that he was not a Jew- struck Hendrick…as immensely comforting. He wasn‘t a Jew, and so everything could be forgiven in him…” continued on the next 1

About Dora Martin, who was a Jewish actress, moving to the US: “”Nothing will change here where you‘re concerned…You are loved by thousands of people…the theater will stay in business…whatever happens in Germany.”…”Well I wish you all the best, Hendrik…I have nothing to look for here…but things will certainly go well fir you, Hendrik Höfgen-whatever else happens in Germany.”

“[Mephisto] was…stronger even than God the Father, whom …he…treated with a somewhat disdainful courtesy. Had he not good reason to look down on Him a little? [Mephisto] was much wittier…wiser, and…unfortunate…; and…there lay the secret of his greater strength - his great misfortune.” The irony for Höfgen trying to be seen as the strongest AND the morally better person by either covering his past or using his misfortunes depending on the situation

“[M. Larue] enjoyed the acquaintance of the most exclusive and reactionary families of Potsdam, and was also seen in the company of left-wing radical young people, whom he liked to introduce in the houses of bank directors as “my young conmunist comrades.” I like the not-so-subtle effect the houses of bank directors brought here; Mann is good with ironies.

“Where is your intellectual tolerance, Herr Privy Councillor? Where are your democratic principles? We no longer recognise you. You sound like a rub-of-the-mill radical politician and not like a man of superior intellect. There is only one way to counter National Socialism - education. We must exert all our efforts to tame these peple through democracy. We must try to win them over…And besides… the Enemy is on the Left.” Classic.

3) The omnipresent third party writing is delightfully tainted by the author‘s own opinions on the main character both through their own description but also through how characters see him, eg Barbara‘s pity, Höfgen being on managers‘ laps to get extra money etc 4) the development of the main character. The themes of self esteem, envy, the parallels between Höfgen on and off stage are so closely aligned that it makes a clear point about himself

Just some ramblings: 1) the depictions of the characters in general are spaced out so well that it feels very organic 2) the most fascinating parts of the storyline involves revelation of a trait and/or a memory,eg: Nicoletta‘s efforts into marrying Barbara off. tbc

She believed herself to be surrounded by the ‘people‘s love‘ because two thousand turncoats, freeloaders and snobs made noise in her honor. She believed in all seriousness that God was on her side bevause he had allowed her to accumulate so much jewellery.

My ‘Mann‘ can‘t look past the fact that everyone is ‘a bit too fat‘. I think I get what he‘s doing but it also keeps on catching me off guard. When it is stated so directly with no context.

“…she occasionally pleaded with her husband for Jews in high social positions - yet Jews were still being sent to concentration camps. Lotte was called the Good Angel of the prime minister; yet his cruelty had become no milder since she had gone to work on him.” The Nazis having performative socialites hadn‘t ever crossed my mind; this shows my naivety in how I saw them as so distinct from us, and how distraught I become to see such parallels now.

Clouds of artificial fragrance had been sprayed in every room, as though to prevent people from inhaling another odour: the stale, sweet stenfh of blood, which permeated the entire country.

“When my aunt had any little occasion to talk to him, to draw his attention perhaps to some mending of his linen or to warn him of a button hanging loose on his coat, he listened to her with an air of great attention and consequence, as though it were only with an extreme and desperate effort that he could force his way through any crack into our little peaceful world and be at home there if only for an hour.” (p20 and p22 on home)

“As for others…he never ceased his heroic and earnest endeavour to love them, to be just to them, to do them no harm, for the love of his neighbour was as strongly forced upon him as the hatred of himself, and so his whole life was an example that love of one‘s neughbour is not possible without love of oneself, and that self-hate really is the same thing as sheer egoism, and…breeds the same cruel isolation and despair.”

“Instead of destroying his personality, [teachers and parents] succeeded only in teaching him to hate himself. It was against himself that…he directed during his entire life the whole wealth of his fancy, the whole of his thought;…every barbed criticism, every anger and hate he could command, he was, in spite of all, a real Christian and a real martyr.”

“A wolf of the Steppes that had lost its way and strayed into the towns and the life of the herd, a more striking image could not be found for his shy loneliness, his savagery, his restlessness, his homesickness, his homelessness.”

“When my aunt had any little occasion to talk to him, to draw his attention perhaps to some mending of his linen or to warn him of a button hanging loose on his coat, he listened to her with an air of great attention and consequence…as though it were only with an extre and desperate effort that he could force his way through any crack into our little peaceful world and be at home there if only for an hour”

The sun sets on the Morisaki Bookshop, wrapping it up with a sheet of golden light, warming my heart with the comfort and feeling of home hidden in each page. Such a comfort book - to be read over and over again.

“All of a sudden, my uncle‘s face lit up-just like a kid who had gotten a wonderful birthday present…it thrilled me even if it was just with someone like my uncle - no, it thrilled me wven more because it was someone like him.” The fact that all of this is on them discussing a book is so… - the smile it put on my face and the warmth it made me feel in my chest

Brilliant writing. The exploration of so many relationships (women and cooking, women and social norms, friendships, parenthood and raising children) done alongside such a subtle character development. Flows so smooth like ‘butter‘ (im sorry). Amazing at the way the perspective from which the book is written engrosses the reader. Let me know what you thought as I really want to talk to someone about this book!

On Rika (and women in general) loving herself: “All you need to do is to eat as much of whatever it is you most desire at any given point. Listen carefully to your body. Never eat anyhting you don‘t want to. When you take the decision to live that way, both your mind and your body will commence their transformation.”

About Kafka‘s work: “Many express remoteness, hopelessness, the impossibility of access to sources of authority or certainty, or what in German is termed Ausweglosigkeit: the impossibility of escape or release from a labryinth of false trails and frustrated hopes.”

I love how Kafka explores heart wrenching themes and changes Gregor goes through (excluding the PHYSICAL metamorphosis) with such an absurd premise. Almost gives the impression that it is the sort of thing your next door neighbour could be going through, and you would never know.

“…he seized in his right hand the stick the clerk had left on a chair … with his left hand took a large newspaper from the table, and began to drive Gregor back into his room by waving the stick and the newspaper at him and stamping his feet. No pleading from Gregor helped, and no one understood him; however meekly he turned his head, his father only stamped his feet harder.” tragedy of Kafka and a Father even of his own creation

“Patrick Wolfe described the settler‘s attitude towards the native as ‘the logic of elimination‘…Classical colonialists saw themselves as bringing modernity to the savages. Settler colonialists saw themselves as modernising the land, not the people.”

“…a pro-Zionist lobby…pious Christians who believed in the ‘return of the Jews‘ to Palestine as fulfilment of God‘s will, antisemites who wanted Jews out of Britain, and Anglo-Jewish aristocrats who would have been loath to immigrate to Palestine themselves, but saw it as a suitable destination for working-class East European Jews…communist troublemakers…the only thing these people had in common was wanting to establish a Jewish state.”

The plotline and its progression are phenomenal… i don‘t know what else to say without spoiling it…

“O, ömrü boyunca hep “acele etmiş”tir; bu yüzden de hrp “geç kalmış”tır. Sürekli bir panik vardır hayatında: Bir kitap okur, bir komedi seyreder, yorulur. Birileriyle birlikte olur, derdini anlatamaz, telaşlanır ve incinir. Küçük dertler, bir yerlere ödenmesi gereken paralar, bazı şeylerin tamir masrafı hiç eksik olmaz ve bu panik duygusuna katkıda bulunurlar. Ve hep acele edilir.” Önsöz, 11. sayfa.

“I replied that you could never change your life, that in any case one life was as good as another and that I wasn‘t at all dissatisfied with mine here. He looked upset and told me that I always evaded the question and that I had no ambition, which was disastrous in the business world. So I went back to work.” For me; an example of how Mersault perceives matters important to the rest of Us as almost light breezes in the air, just passing him by.

“I felt like telling her that [mother‘s death] wasn‘t my fault, but I stopped myself because I remembered that it wasn‘t my fault, but I stopped myself because I remembered that I‘d already said that to my boss. It didn‘t mean anything. In any case, you‘re always partly to blame.”

“I remember a few other scenes from that day as well: for instance, Pérez‘s face when he caught up with us for the last time just outside the village. Great tears of frustration and anguish were streaming down his cheeks. But because of all the wrinkles, they didn‘t run off. They just spread out and ran toggether again, forming a watery glaze over his battered old face. Then there was the church and the villagers in the street, the red geraniums..

“Nesnelerin insana dokunmaması gerekir çünkü onlar canlı değildir. Aralarında yaşar, onları kullanır, sonra yerlerine koyarız: Yararlıdırlar, işte o kadar. Oysa bana dokunuyorlar. Çekilmez bir durum bu. Onlara bağlantı kurmak korkutuyor beni. Sanki hepsi birer canlı hayvan gibi…Bu duygunun çakıltaşından geldiğinden, ellerime ondan geçtiğinden kuşkum yok…ellerde duyulan bir tür bulantı bu.”

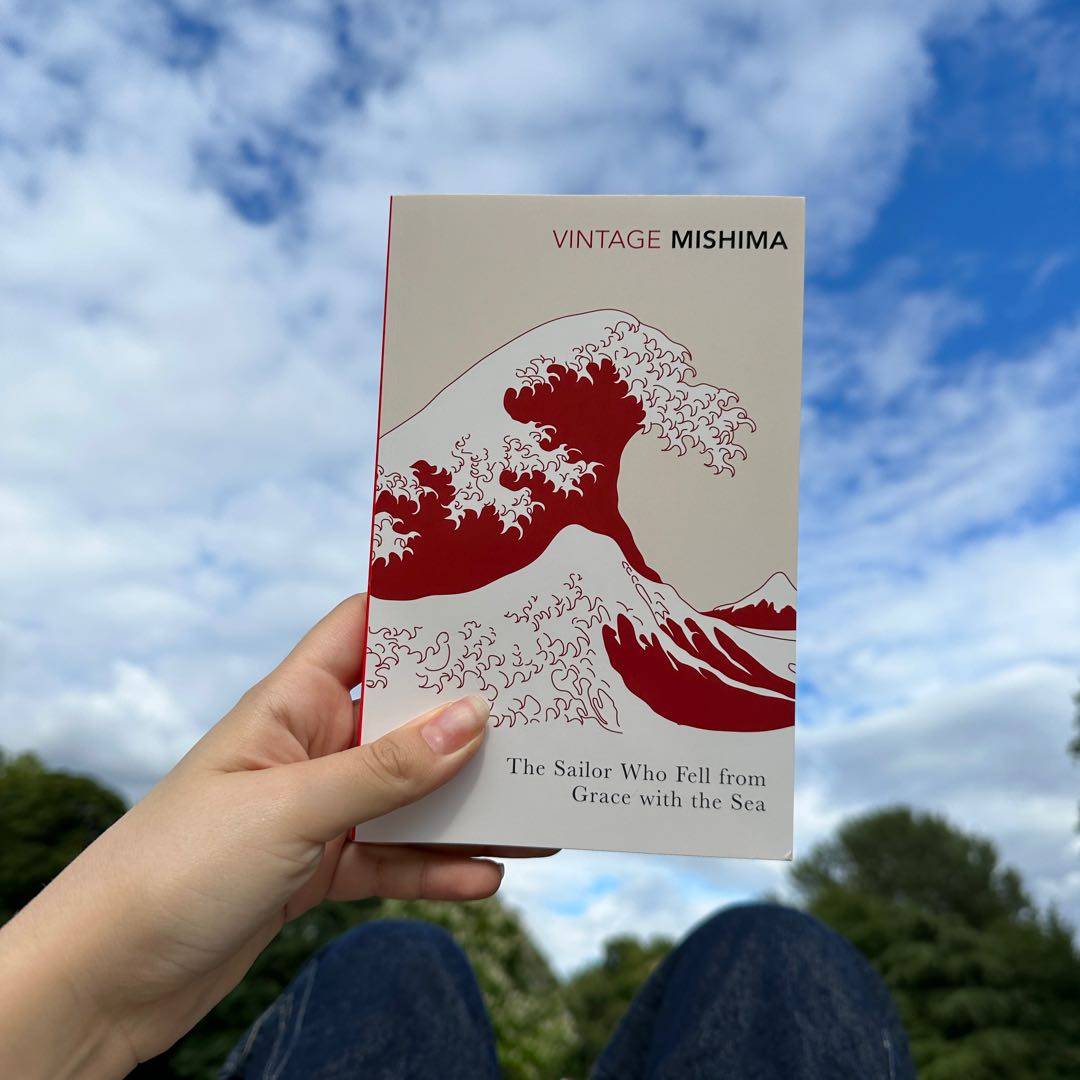

The plot flowed so subtly; something so horrible hiding itself behind the the façade of a child being a mere child. The spectrum of glory, on which stood one 13 year old and one 30-something year old, mirroring one another, was beautifully done. The exploration of masculinity, obsession and more, through seemingly two different lenses was so beautifully done. I would love to read a book just on each and every single one of the characters on here.

Fusako on Ryuji (ie the prototype of masculinity according to both himself and Noboru): “…what a simple man he was!… First he had misled her with his pensive look ubfi expectibg profound observations or even a passionate declaration, and then he had begun a monologue on shreds of green leaf, and pratted about his personal history, and finally, horribly entangled in his own story, burst into the refrain of a popular song!”

The character development, the maintenance of the flow despite the time jumps…I am once again in love with LeGuin‘s ability to note the intricacies of that period, and I absolutely loved it. It reminded me of how 1984 was apparently banned in both the US and the USSR for spreading counter ideologies. This is definitely a book to be read over and over again and find new details, nuanced you probably missed the previous read.

“He could not force himself to understand how banks functionaled and so forth, because all the operations of capitalism were as meaningless to him as the rites of a primitive religion, as barbaric, as elaboratr, and as unnecessary. In a human sacrifice to deity there might be at least a mistskrn and terrible beauty; in the rites of moneychangers, where greed, laziness and envy were assumed to move all men‘s acts, even the terrible became banal.”

“The rest of us keep pretending we‘re happy or else just go numb. We suffer, but not enough. And so we suffer for nothing.”

One of the best world-building I read in a long time; the intricate detailing of Le Guin does not suffocate; it is as fresh as Winter itself. Same goes for character building. The use of stark contrasting - between countries, between landscapes, between characters - was done so smoothly that I both felt like I was going back and forth yet within the given world of Gethen still - nothing felt detached.

“How does one hate a country, or love one? I know people…I know how the sun at subse tin autumn falls on the side of a certain plowland in the hills; but what is the sense of giving a boundary to all that, of giving it a name and ceasing to love where ghe name ceases to apply? What is love of one‘s country; is it that of one‘s uncountry?…that sort of love does not have boundary-line of hate.”